CS research that attempts to represent privacy typically takes one of two approaches: policy based proposals and / or ontological frameworks.

Policy

The policy-based research generally falls within privacy policy creation, breaches and assessment processes. Popp and Poindexter focus on the creation of policies, arguing for the coordination of security and privacy policies (Popp & Poindexter, 2006). They present a proposal for countering terrorism through information and privacy-protection technologies originally part of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) research and development agenda as part of the Information Awareness Office (IAO) and the Total Information Awareness (TIA) program. These programs were respectively based on the hypothesis that the prevention of terrorism was based on the acquisition of information used to determine patterns of activity indicative of terrorist plots. This information is both collected and analyzed, and the authors proposed that privacy protections can and should be implemented as part of both of these activities. The paper provides quantitative data demonstrating that time spent on the analysis phase of intelligence activities can be exponentially increased using IT methods, which also eliminate siloes in information analysis (generally agreed to be one of the problems resulting in the failure to prevent the September 11 2001 attacks).

While assessments are a relatively well-researched topic in privacy (in particular outside the discipline of CS), there are few privacy breaches studies that go beyond incident rates. Liginlal et al present a unique empirical study on the causality of privacy breaches based on the GEMS error typology (Liginlal, Sim, & Khansa, 2009). The use of traditional models of human error from the 1990s fits well with privacy breaches, and results in an easily applicable 3 step method for defending against privacy breaches (error avoidance, error interception and error correction). While the authors’ conclusion is not unique in privacy policy circles, basically that different systems need to be built differently to mitigate the risk of human error, they do present a robust research paper in an under-researched sub field of policy that can be applied to any industry or sector that is involved in information processing activities subject to privacy legislation.

Ontology

Three different approaches to privacy ontologies are evident in CS:

- Policy enforcement based (Hassan and Logrippo’s ontology for privacy policy enforcement (Hassan & Logrippo, 2009a))

- Industry specific (Hecker’s privacy ontology to support e-commerce (Hecker, Dillon, & Chang, 2008)), or

- General to the legislation (Tang’s privacy ontology for interpreting case law (Tang & Meersman, 2005)).

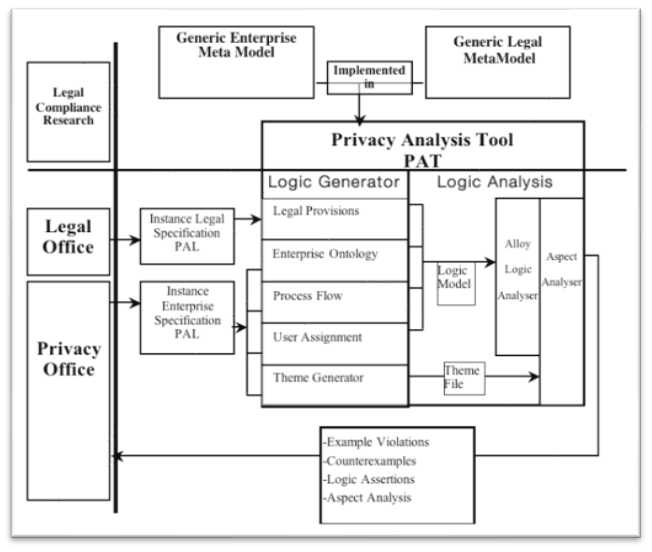

The privacy policy enforcement ontology is built on much of the policy-based research in CS, so its applicability varies; for example, the ontology proposed by Hassan and Logrippo is based on a set of privacy principles specific to Canada so it could only be applied in this jurisdiction. This type of ontology can provide examples of possible violations of privacy policy, counterexamples (for preventative policy actions), logic assertions and theme analysis. A schematic form of the model is provided:

Privacy Analysis Tool Schematic (Hassan & Logrippo, 2009a)

This ontology is somewhat limited because of the jurisdictional construct. However, the use of formalized representation to represent legal requirements shown are helpful in converting legal requirements into the logical assertions required by the tool for analysis, including structural, flow and dictionary information.

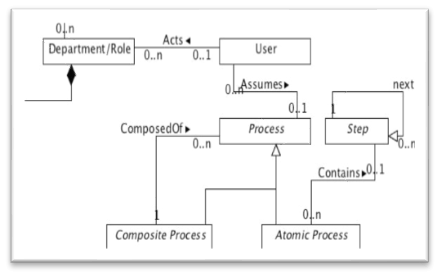

Meta-Model with Process Ontology (Hassan & Logrippo, 2009b)

Curiously, Hassan and Logrippo note that “our approach is far from covering all aspects of privacy legislation, in fact we are not even trying to approach such completeness, since ethical, social and other aspects can be impossible to represent in logic-based semantics” (Hassan & Logrippo, 2009a). Yet, the process ontology proposed in purports to accomplish just that in order to calculate privacy policy enforcement.

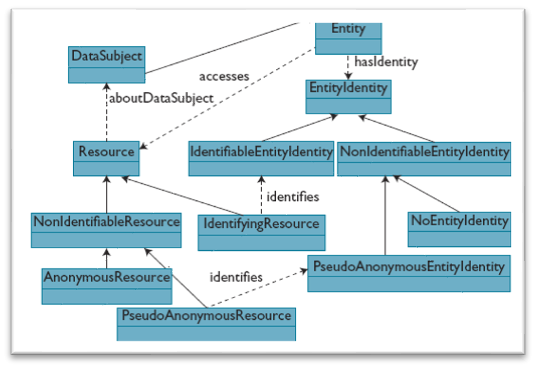

Hecker et al works include similar process ontology, but also includes the entity relationships:

Privacy Ontology with Entity Hierarchy (Hecker et al., 2008)

This four step process results in a process based ontology, which can identify the resources and data subject. Finally, with the addition of the entity, the privacy ontology provides the basis for an entity hierarchy. The success of this approach depends on privacy policy abstraction, which the authors propose so that record types, resources elements and concept domains are all accounted for. They note that much of this work can be borrowed from other domains, to ease both the database requirements and computational processing resources once implemented.

Hecker et al’s unique contribution to the field is found in the rationale for the privacy ontology. The authors paraphrase; privacy on the web faces massive problems due to two major factors: first, “the inherently open, nondeterministic nature of the Web”; second the “complex, leakage-prone information flow of many Web-based transaction that involve the transfer of sensitive, personal information” (Hecker et al., 2008).

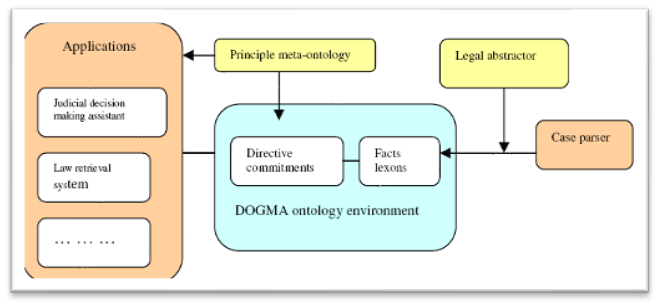

Tang and Meersman set out to apply ontological technology directly to regulated privacy requirements, by linking case law and legislation (Tang & Meersman, 2005). The proposed ontology is set out:

Privacy Ontology Structure (Tang & Meersman, 2005)

The directive commitment consists of fact proving, syntax interpreting, interpretation and justification and fact reasoning to undertake case analysis.

The legal abstractor bridges the case parser and the ontology. The authors describe the data as including law retrieval systems with a privacy sub-directive retrieval system and the e-court system (to retrieve documents from the court debate system).

The case parser is the basis of the legal ontology data. In this environment, the proposed ontology would be represented by fact lexons (extracted from case law) and the directive commitments (that tailor fact lexons to ascribing real life application requirements). Tang and Meersman are some of a very few researchers in the ontological field of privacy that propose a development environment: DOGMA (Developing Ontology-Guided Mediation for Agents), as it separates concepts and relations from constraints, derivation rules and procedures (Tang & Meersman, 2005).